Battle of Long Tân: A 1,500-Strong Viet Cong Force Ambushed 108 Australians – They Lost

At the height of the Vietnam War, 108 Australian soldiers stood against a force of between 1,500-2,500 Viet Cong guerrillas near the village of Long Tân. When the engagement, dubbed the Battle of Long Tân, was over, the former force had lost 18 men, while another 21 were wounded. The enemy, however, may have suffered hundreds of losses.

While the Australians came out victorious against overwhelming odds, the country’s government was quite stingy about giving the troops the recognition they deserved.

Separating themselves from the American forces

Australian soldier serving in Long Phước during the Vietnam War. (Photo Credit: US Military Personnel / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

In 1965, Australia already had a presence in Vietnam, albeit under American control. This way of operating was quite contentious, as the Australians didn’t necessarily agree with, nor were they used to, the attrition warfare used by the American forces. Among the military brass, it was believed the guerrilla tactics they’d mastered during the Malayan Emergency were much more effective, leading them to set up their own base.

This new military post was set up in the province of Long Phước, a well-known Viet Cong stronghold. It also had a port that gave them the freedom to move troops in and out at will, and it had terrain that could be easily navigated by veterans who’d served in Malaya.

The chosen site was known as Núi Đất and was operated by the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF). Commanded by Brig. Oliver David Jackson, a 4,000-meter exclusion zone known as Line Alpha was established, resulting in local residents being expelled from the area. This was to ensure Viet Cong guerrillas couldn’t masquerade as everyday citizens.

Viet Cong guerrillas launch a surprise attack

Soldier with the 6th Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR) firing an RPD machine gun captured during the Battle of Long Tân, 1966. (Photo Credit: William James Cunneen / Australian War Memorial / Wikimedia Commons CC0 1.0)

By August 1966, the base was barely three months old and not entirely ready. Knowing this and hoping to dislodge it, the Viet Cong, positioning themselves at a nearby rubber factory, began their offensive. The Australians picked up radio transmissions hinting that something was in the works, but sweeps of the area found nothing.

As August 16 gave way to next day, Núi Đất was attacked by 82 mm mortar fire, 70 mm howitzers and 75 mm recoilless rifles. The Australians responded with counter-battery fire, with both sides engaging each other until the next morning, before it died down.

The location where the guerrillas had fired from was later discovered by a sweep. While abandoned, the Australian troops did find clothes and blood stains, proving that their return fire had hit some of the enemy fighters.

Initiating the Battle of Long Tân

Australian artillerymen with the 103rd Field Battery firing a 105 mm L5 PACK Howitzer at Núi Đất, 1966. (Photo Credit: Australian War Memorial / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

The Australians, now feeling secure, set up patrols of the area and returned to Núi Đất. At approximately 11:00 AM on August 16, 1966, the 108-man D Company, 6th Battalion, 6th Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR) and a three-man New Zealand artillery forward observer left the base to relieve B Company, which had been tasked with patrolling the jungles around the rubber plant.

Reaching the site at around 1:00 PM, D and B Companies had lunch together, before the latter returned to base. At that point, a small detachment from D Company went on patrol, coming across a group of between six and eight Vietnamese men dressed in green uniforms at 3:40 PM. Luckily for the Australian troops, the men didn’t notice them – that is, until Platoon Sgt. Bob Buick fired a shot. This prompted the others to scatter.

While the encounter was reported to Núi Đất, the Australians didn’t immediately realize what they were up against. They were facing contingents of the Viet Cong – the 275th Regiment and D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion, to be exact.

Attacked by the Viet Cong (again)

Second Lt. Dave Sabben moving through the area around the rubber plant the day after the Battle of Long Tân, 1966. (Photo Credit: Australian War Memorial / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Shortly after resuming the advance, at 4:08 PM, D Company’s 11 Platoon, having drawn ahead of the others, came under small-arms and rocket-propelled grenade fire from an unseen group of Viet Cong guerrillas. The deadly ambush, made worse by the limited visibility that arose as a monsoon storm rolled in, led them to call for artillery support.

Heavy fighting subsequently ensued as the advancing fighters of the Viet Cong’s 275th Regiment and D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion attempted to encircle and destroy the Australians. After less than 20 minutes, over a third of 11 Platoon had been hit, some perishing from their injuries.

Núi Đất responded by heavily shelling the Viet Cong’s positions, but air support was out of the question. Officials at the base also weren’t willing to ask the Americans for assistance. It soon became clear, however, that they weren’t completely aware of the full number of enemy troops beginning to flank D Company.

Reinforcing D Company, 6th Battalion, 6th Royal Australian Regiment

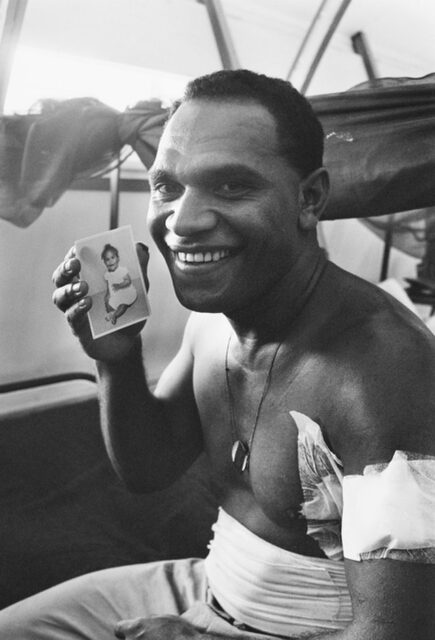

Cpl. Tom “Buddy” Lea, who was injured during the Battle of Long Tân, 1966. (Photo Credit: Australian War Memorial / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

10 Platoon tried to move to the left in support, but was repulsed by the Viet Cong guerrillas. With D Company facing a much larger force, 12 Platoon tried to push up on the right at 5:15 PM. Fighting off an attack on their right before pushing forward another 110 yards, they sustained increasing casualties after clashing with several groups.

Opening a path to 11 Platoon, but unable to advance further, 12 Platoon threw red smoke to mark their location. At 6:00 PM, when they were nearly out of ammunition, two Bell UH-1B Iroquois from No. 9 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) arrived to resupply D Company.

Meanwhile, the survivors from 11 Platoon withdrew to 12 Platoon during a lull, suffering further losses. Still heavily engaged, both then moved back to the company position, covered by artillery. By 6:10 PM, D Company had re-formed, but was still in danger of being overrun. A Company, 6 Royal Australian Regiment was dispatched in M113s from 3 Troop, 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) Squadron to reinforce them.

B Company headquarters and one platoon were still returning to Núi Đất, at which point they were also ordered to assist.

Turning the tide of the Battle of Long Tân

Bell UH-1D Iroquois with the No. 9 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), 1970. (Photo Credit: USAF / U.S. Air Force Historical Studies Office / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Leaving Núi Đất at 5:55 PM, the armored personnel carriers moved east, crossing a swollen creek before encountering elements of the D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion attempting to outflank D Company and assault the men from the rear. The guerrillas were caught by surprise as the other Australian troops crashed into them and, with darkness falling, they broke through, while B Company entered the position at 7:00 PM.

The relief force wound up turning the tide of the Battle of Long Tân. The Viet Cong had been looking to launch another attack that very likely would have destroyed D Company, but the firepower and mobility of the recently-arrived Australian troops broke their will, forcing them to withdraw.

The artillery barrage had been almost constant throughout and proved critical in ensuring the survival of D Company. By 7:15 PM, the firing had ceased and the Australians awaited another attack. However, after none occurred, they began their preparations to withdraw 750 meters to the west.

With the dead and wounded loaded up, D Company left the area at 10:45 PM. B and Companies departed on foot. A landing zone was then established by the cavalry, with the evacuation of the casualties finally completed after midnight. Forming a defensive position ready to repulse an expected attack, they remained overnight, enduring the cold and heavy rain.

On heightened alert

Site where the Battle of Long Tân took place, 2005. (Photo Credit: Tacintop / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

The Australians returned in strength the next day, sweeping the area and locating a large number of Viet Cong dead. They had initially believed they’d suffered a major defeat, but as the scale of the guerrillas’ losses were revealed, it became clear they had scored a significant victory.

Two wounded Viet Cong were killed after they moved to engage the Australians, while another three were captured. The bodies of the missing from 11 Platoon were also located. Two members had survived, despite their wounds, after having spent the cold, dark night in close proximity to the guerrillas as they attempted to evacuate their own casualties.

Due to the likely presence of a sizeable force nearby, the Australians remained cautious as they searched for the Viet Cong. Over the next two days, they continued to clear the battlefield, uncovering even more deceased enemy fighters. However, with the 1st Australian Task Force lacking the resources to pursue the withdrawing force, the operation ended on August 21, 1966.

A decisive Australian victory

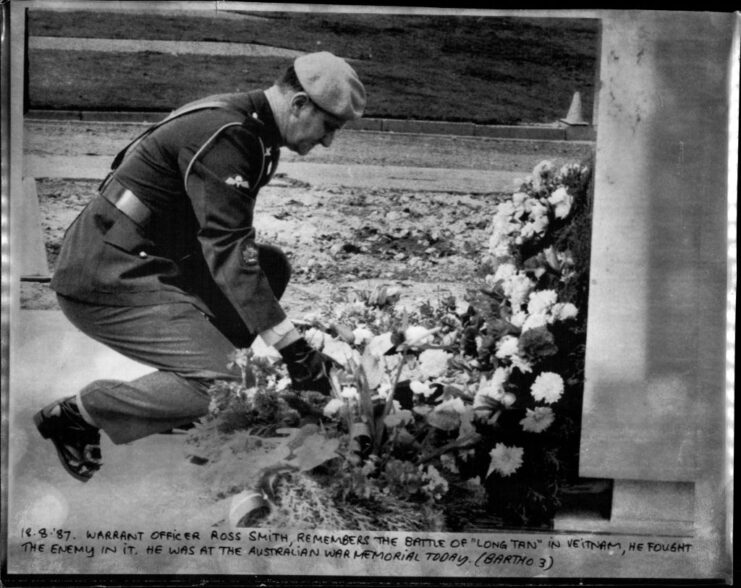

Warrant Officer Ross Smith remembering the Battle of Long Tân during a visit to the Australian War Memorial, 1987. (Photo Credit: David James Bartho / Fairfax Media / Getty Images)

Heavily outnumbered, but supported by strong artillery fire, D Company held off a regimental assault before a relief force of cavalry and infantry fought their way through and forced the Viet Cong to withdraw. Eighteen Australians were killed and 21 wounded, while the enemy had suffered at least 245 dead.

A decisive Australian victory, the Battle of Long Tân proved to be a major local setback for the Viet Cong, indefinitely stalling an imminent movement against Núi Đất. While there were other large-scale encounters, the 1st Australian Task Force wasn’t really challenged again.

Unfortunately, as Australia still used the Imperial Honours System, which was based on quota, there was a limit to the number of medals that could be handed out for the engagement. This resulted in veterans receiving mere commendations or nothing at all. As reviews have been conducted in the decades since, several of the men who fought at the Battle of Long Tân have been awarded medals that should have been theirs back in 1966.